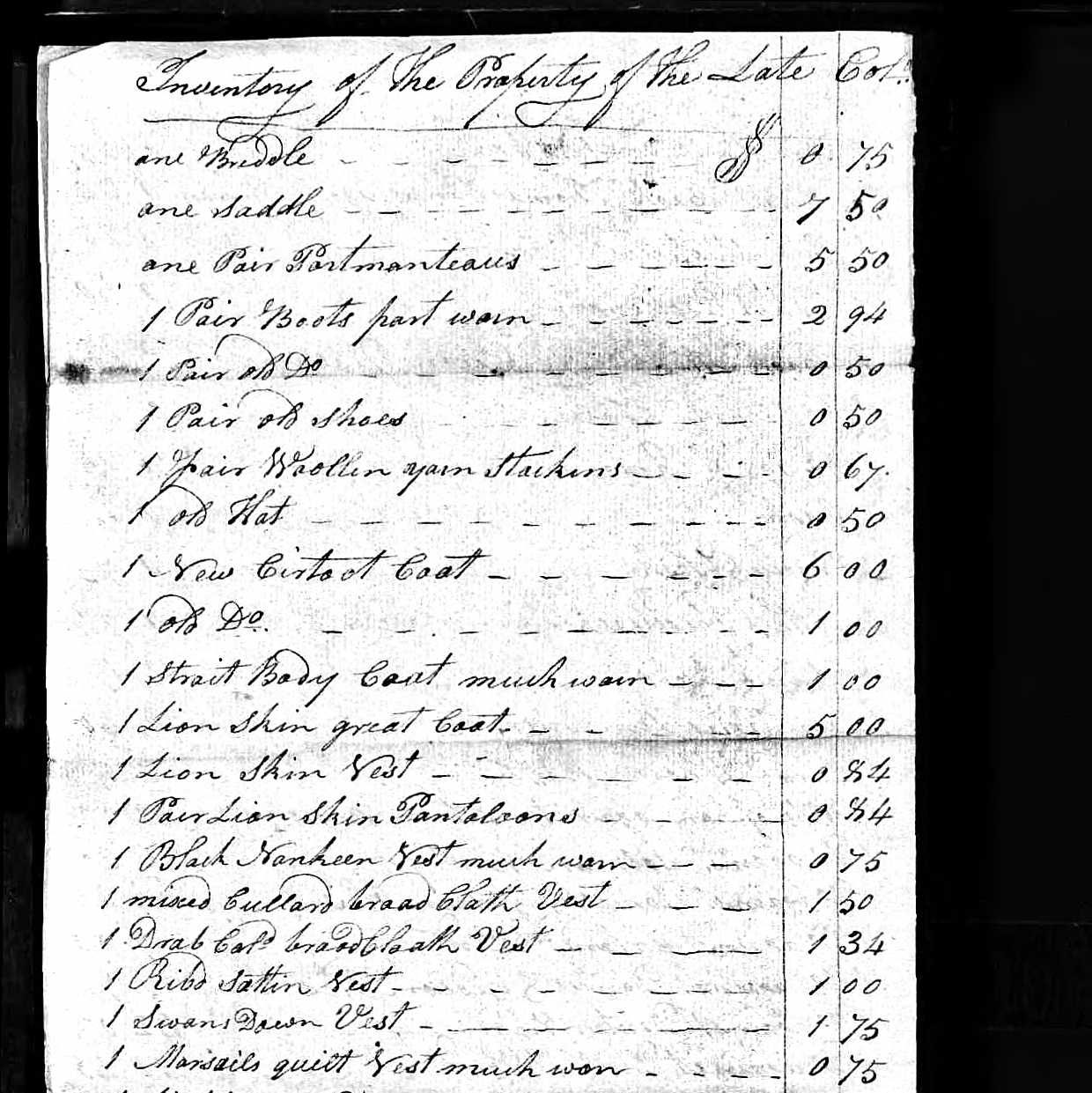

Probate records of estate inventories can provide us with a glimpse into the daily life of a time and place. Here is part of the estate of Lt. Col. Udney Hay who lived in Underhill 1796-1806. Some items of note:

1 Lion skin great coat and 1 lion skin vest: Despite his affiliation with the Democratic Republican Party ostensibly opposed to the aristocratic trappings of monarchy, Hay seems to have still appreciated some of the finer luxuries which might showcase his status as a gentleman.

Hay owned not one, but two copies of Thomas Paine’s wildly popular Age of Reason. Hay had publicly voiced support for Paine during his campaign for U.S. Congress 1802-1803

https://vsara.newspapers.com/image/488980182

Udney Hay Obituary

From the Vermont Centinel, September 10th, 1806:

With the deepest regret we announce to the public the death of Colonel Udney Hay, which took place in this town on Saturday the 6th ins. after a very short illness, in the sixty seventh year of his age. The next day his remains were conveyed to the meeting house, where an appropriate discourse was delivered by the Rev. President Saunders and attended to the grave by a numerous and respectable procession of his friends, from this and the neighboring towns, with uncommon manifestations of regard for his character and sorrow at his death. As a member of the council of Censors, the loss of Col. Hay, is to the state of Vermont at this time peculiarly irreparable, and must excite an unusual share of public regret.

We are aware that commendation of the dead is often and sometimes perhaps justly suspected of disguising real faults, and embellishing with counterfeit virtues; but the character of Col. Hay needs no fictitious coloring. His illustrious worth, like the sun, was crowned with its own beams and diffused its influence throughout a very broad circle. Though his life was a checkered scene—a twilight mixed with shadows—his virtues were such as ennobled while they endeared; for with honor which felt a stain like a wound, he combined integrity that palsied suspicion, and a philanthropy always glowing—but which quickened as he advanced in life, and seemed cubed for perpetuity. In fixing his destiny, nature and fortune seem to have been at perpetual war. The first had selected him as a favorite of her own, while the last early fastened her basilisk frown to pall his hopes and blast his expectations. Unfortunately, nature’s rare gifts are seldom found unalloyed with correspondent weakness—and Col. Hay’s open ingenuous spirit would have procured him enemies had he not been blessed at the same time with a goodness and sincerity of heart that would bear inspection, and which magnet-like, attracted as you approached it. Wit and judgement are not often united—but in Col. Hay they seemed to be kindred powers, most intimately interwoven and mutually cooperating, assisting and correcting each other. His wit was facetious, seldom severe, and rather courted a smile than imparted a sting. His judgment was penetrating, solid, and firm, his apprehension quick and clear, his imagination unusually vigorous and sprightly, but always obedient to reason. To these were united a generous warmth of friendship and gratitude, which stood fixed at a perpetual summer solstice—and benevolence so active, so expansive that it beggared, as it were, every other quality of his heart.

These were the gifts of nature, and with these had his situation and circumstances corresponded, what would he not have been! There is something, however, sublime in the contemplation of a great mind struggling with fortune, and Hercules-like, shaking off the calamities she has sent to subdue it.

In early life, Col. Hay came to America without education, without property or friends. During our Revolutionary War he soon and long distinguished himself in the department where he was stationed as an active, enterprising and able officer. And since the establishment of our State, his influence in our public councils for a considerable number of years, has been predominant beyond a parallel. As a politician his views of public affairs were marked with an amplitude of thought that spoke the man of prospect and profound sagacity. With a sovereignty of mind, that soared above the petty motives which tempt little souls from a straight course—he early adopted a system, and adhered to it with unwearied pertinacity to the end. If at any time, he had the zeal of a partizan it was without asperity—and his political adversaries however they may deprecate his influence, must bear testimony to his sincerity of opinion and he suavity of his manner in debate—never vehement or overbearing, preceptive of reason and open to conviction. To crown the whole, Col. Hay was a philosopher—his disposition was moulded for the blandishments of domestic life and “soft collar of social esteem”—but adversity, here pierced his heart through without freezing his spirits. His philosophy did not shrink from the calamities of life. It was not of that “dry fastidious sort that involved itself in a labyrinth of empty notions and logical subtleties, but of that authentic, plain, and practical kind that regulates the feelings, while it interests the heart, that corrects our wanderings while it stimulates our enquiries, that teaches us how to live and how to die, by teaching us what we are and for what we are designed.” With this philosophy he faced death without dismay, and with this philosophy we firmly believe he will be supported, when the bigotry of superstition shall pass away with the blaze of the Universe.